Texte : Denis Lejeune

Quand on évoque les “valeurs” de l’escalade, la notion d’amitié, d’esprit de cordée, de partage ne font pas partie des moindres. Il est vrai que le rocher a le don de forger des liens qui, quand ils comptent, durent une vie, justement parce que c’est la sienne que notre assureur tient entre ses mains (et inversement). Il y a les cordées mythiques, “Sonia” et Georges Livanos, les deux Patrick (Berhault et Edlinger), les frères Huber, Babsi Zangerl et Jacopo Larcher ; on se souvient aussi de cette célèbre photo de Fred Beckey faisant du stop avec une pancarte disant “Will belay for food”, indiquant un rapport différent mais néanmoins fort à l’altérité.

Et pourtant l’escalade se décline également au singulier. Historiquement d’abord, la grimpe en solo a toujours constitué une part non-négligeable de l’activité. Il y eut Paul Preuss bien sûr, un de ses premiers thuriféraires, mais son ombre semble parfois occulter le fait qu’elle n’est pas née avec lui, ni morte lors de sa dernière chute. Les Dolomites et les Alpes ont vu moult exploits en solitaire, qu’on pense à Bonatti, Comici, Profit, Hansjörg Auer ou encore Ueli Steck. Dans le Peak District anglais et en Écosse, le solo intégral fait partie de l’ADN local, et nombreux sont ceux qui s’y adonnent au moins de temps à autre, tels que Pete Whittaker ou Dave McLeod, lesquels vloggent allègrement sur le sujet. Enfin, on ne peut parler de solo aujourd’hui sans mentionner Alex Huber ni Alain Robert, encore moins Alex Honnold, dont la célébrité entière repose sur d’ébouriffantes solitaires en big wall.

Avant de chercher à savoir pourquoi le solo, il convient de distinguer les trois formes qu’il prend afin d’éviter les confusions. D’abord le solo intégral : des chaussons et de la magnésie, rien d’autre (sauf dans les cas où le grimpeur garde une corde dans son sac pour la descente, ou comme dernier recours). Ensuite les deux types de solo encordés : la tête auto-assurée (TAA), et la moulinette auto-assurée (MAA). Elles peuvent avoir d’autres noms. Dans ces deux cas le grimpeur escalade seul mais, comme dans l’escalade à deux, il est bel et bien assuré—il est safe.

Autant le solo intégral brille par sa simplicité (c’est d’ailleurs une des raisons pour lesquelles la discipline est tant appréciée), autant à l’heure de la redondance le TAA et le MAA requièrent a minima un doctorat. Vous voilà prévenus.

Pourquoi le solo ? Pour la variante intégrale, voyez avec Honnold. Pourquoi alors le solo encordé ? Pour des raisons pratiques d’abord : à l’heure des horaires flexibles, pas toujours facile de trouver un assureur dévoué quand on sort du travail. Dans une optique de partage, on laisse tomber le plan falaise et on fait du pan dans son coin (seul donc). Mais pourquoi ne pas aller en falaise anyway ? N’est-ce pas plus marrant, et beau, et apaisant ? Pourquoi se priver d’un tel plaisir au motif qu’un seul être vous manque et tout serait dépeuplé ?

Quid de votre gros projet commencé il y a trois ans ? Pourquoi soudoyer une lointaine connaissance voire un parfait inconnu pour qu’il s’endorme sur son Grigri après votre 27ème repos dans le crux, alors qu’il serait si simple de poser vos nœuds de 9 au relais et de bosser votre voie comme un grand solitaire ? Il en va de la santé mentale de votre entourage parfois, alors passez le cap.

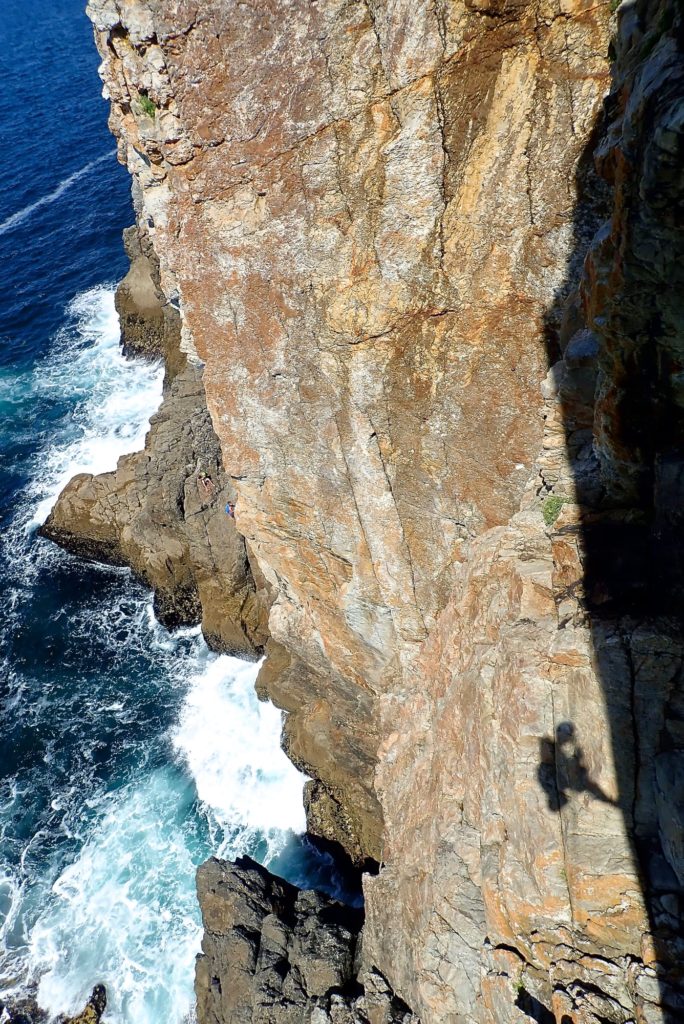

En terme d’équipement et de manip, le free solo et les autres n’ont rien à voir. En revanche, là où les trois se rejoignent, c’est dans le plaisir qu’on peut en retirer, une sorte de retraite du monde des hommes pour se retrouver entièrement lové dans la nature, végétale et minérale. Nul doute que le solo intégral amplifie encore ces sensations océaniques, du fait de l’épée de Damoclès qui pendouille sans arrêt au-dessus de votre tête, mais même en étant en parfaite sécurité ce tête-à-tête avec le monde est rendu possible, justement parce que vous êtes seul. Personne pour vous poser des questions, vous rappeler une course à faire ou vous donner des méthodes pourries ; personne à qui sourire, dont on veut éviter le regard ou les non-dits ; personne à qui on se sent obligé de raconter une blague : le fardeau de la sociabilité s’est évanoui, vous n’êtes plus en représentation, vous n’avez personne à charmer ou à qui plaire ; votre timidité est au rebut ; pas de gros blancs pesants.

Vous pouvez enfin être vous-même, vous plonger dans vos pensées ou un large désert intérieur, ouvert aux vents de la falaise. Pour une fois il vous est possible de vous consacrer exclusivement à ce que vous faites—ce qui n’est pas un mal étant donné la complexité de vos opérations et le coût exorbitant d’une erreur que personne d’autre que vous n’est là pour pointer du doigt. Et aux environs, aux branches qui frémissent, à la terre qui sent, au rocher qui vous regarde avec amusement et pitié ; au ciel, aux insectes nonchalants. La vie change de rythme, seul, elle ralentit, son pouls passe enfin sous les 40 battements par minute, il n’y a plus de bruit dans vos oreilles et votre esprit se repose : il soupire un soulagement qu’il garde au fond depuis, pfiou, au moins.

Votre rapport au minéral change également. Vous vous retrouvez plus à son écoute, puisque vous avez enfin le temps de vivre, votre seul impératif consistant à prendre plaisir dans ce que vous faites. Dès qu’on escalade en solo un dialogue d’une autre nature s’instaure entre vous et le rocher ; ce n’est pas qu’il change de visage, mais une forme de masque vient de tomber.

Et enfin, pour les inquiets (ou les addicts) du beta spraying, se lancer en solo sur une falaise déserte, c’est l’assurance de devoir trouver les solutions soi-même. C’est le retour aux sources, le face-à-face avec soi-même : aucun consumérisme ici, ce que vous obtiendrez viendra de vous, et de vous uniquement—méthodes géniales et pourries tout autant. L’aventure quoi.

En bref, on arrive souvent au solo encordé par défaut, on progresse pour son côté pratique, mais on y reste par bonheur.

Photos : Alex Needham, Kuba Klos et Denis Lejeune

Text by Denis Lejeune

When we talk about the ‘values’ of climbing, the concept of friendship, the rope-up spirit and the idea of sharing are some of the overarching ones. It is true that the rock has a knack of creating human links that, when they matter, last a lifetime. Some of those roped parties have gone down in history: ‘Sonia’ and Georges Livanos, the two Patricks (Berhault and Edlinger), the Huber brothers, Jacopo Larcher and Babsi Zangerl; we also remember the famous picture of Fred Beckey hitchhiking with a sign reading ‘Will belay for food’-a different rapport to alterity for sure, yet again highlighting its importance.

Even so, climbing also works in the singular. Historically, solo climbing has always been an integral part of the activity. There was Paul Preuss of course, one of its first advocates, but his towering presence sometimes seem to hide the fact that solo climbing wasn’t born with him, nor died during his last fall. The Dolomites and Alps have seen many a solo exploit, whether it be Bonatti, Comici, Profit, Hansjörg Auer or Ueli Steck, to name but a few. In the Peak District and in Scotland, free soloing is part and parcel of the local DNA, and many partake from time to time, Pete Whittaker or Dave McLeod for instance, who both vlog freely on the subject. Finally, we cannot possibly talk about soloing today without mentioning Alex Huber, Alain Robert, and even less Alex Honnold, whose fame rests solely on his insane free solos on big walls.

When we talk about the ‘values’ of climbing, the notions of friendship, ‘rope spirit’, of sharing are not among the lesser ones. It is true that the rock has a way of forging ties that, when they matter, last a lifetime, maybe because it is one’s life that the belayer holds in his hands, and vice-versa. History is littered with famous partnerships: ‘Sonia’ and Georges Livanos, the two Patricks (Berhault and Edlinger), the Huber brothers, Babsi Zangerl and Jacopo Larcher… There is also that famous picture of Fred Beckey hitchhiking with a sign reading ‘Will belay for food’, which shows a different, yet no less powerful rapport to the Other.

And yet, climbing also works in the singular. Historically, solo climbing has always been an integral part of it. With Paul Preuss of course, one of its first and most vocal proponents, but his shadow sometimes seem to hide the fact that it wasn’t born with him, or die in his last fall. The Dolomites and the Alps have witnessed a great many solo exploits: we only have to think of a Bonatti, a Comici, a Profit, a Hansjörg Auer or a Ueli Steck, to name but a few. In the Peak District and Scotland too, free soloing is part and parcel of the local DNA, and many partake at least from time to time, such as Pete Whittaker or Dave McLeod, who both enjoy vloging about it.Finally, impossible to talk about soloing today without mentioning Alex Huber, Alain Robert and Alex Honnold, whose fame rests solely on his hair-raising climbs on big walls.

Before trying to find out why solo, it is necessary to distinguish its three forms in order to avoid confusion. First, free solo: climbing shoes and chalk, nothing else (except in cases where the climber keeps a rope in his bag for the descent, or as a last resort). Then the two types of roped solo: lead rope solo (LRS), and top-rope solo (TRS). They may have other names. In these two cases the climber is alone but, as in partnered climbing, they are well and truly belayed—safe.

Whereas free solo shines by its simplicity (this is one of the reasons why the discipline is so appreciated), in our times of redundancy, TRS and LRS require at least a doctorate. You have been warned.

But why solo? For the free variant, see with Honnold. So why rope solo? For practical reasons first: in the age of flexible working hours, it is not always easy to find a dedicated belayer when you finish working. If we are dead set on the sharing part of climbing, we therefore have to drop the crag plan and get stuck in with our fingerboard (alone then). But why not go cragging anyway? Isn’t that more fun, and beautiful, and soothing? Why deprive yourself of such pleasure on the grounds that only one being is missing and everything should be depopulated?

What about your big project started three years ago? Why bribe a distant acquaintance or even a complete stranger to fall asleep on their Grigri after your 27th rest in the crux, when it would be so easy to stick your fig 9 knots at the chains and work your way like a great solitaire? The mental health of those around you sometimes depends on it, so go ahead.

In terms of gear and rope technique, free soloing and the others have nothing in common. On the other hand, where the three come together is in the pleasure that one can derive from it, a sort of retreat from the world of men to find oneself entirely immersed in nature. There is no doubt that free soloing amplifies these oceanic sensations even more, because of the sword of Damocles which constantly dangles above your head, but even while being in perfect safety this one-on-one with the world is made possible, precisely because you are alone. Nobody to ask you questions, remind you of an errand to run or give you rotten methods; no one to smile at, whose gaze you want to avoid; no one you feel compelled to tell a joke to: the burden of sociability has faded, you are no longer on show, you have no one to charm or please; your timidity is discarded; no big and heavy silences.

You can finally be yourself, immerse yourself in your thoughts or your wide internal desert, open to the winds of the crag. For once it’s possible for you to focus exclusively on what you’re doing—which isn’t a bad thing given the complexity of your operations and the exorbitant cost of making an error that no one is there to point out to you. And to the surroundings, to the quivering branches, to the earth that smells, to the rock that looks at you with amusement and pity; to the sky, to the nonchalant insects. Life changes rhythm, alone, it slows down, its pulse finally goes below 40 beats per minute, there is no more noise in your ears and your mind finally rests: it sighs a sight of relief that it has kept deep down since, phew, at least.

Your relationship to the mineral also changes. You find yourself more attentive to it, since you finally have time to be, your only imperative being to take pleasure in what you do. As soon as you climb solo, a dialogue of another nature is established between you and the rock; it’s not that it changes face, but a form of mask just fell off. And finally, for those worried (or addicted) to beta spraying, going solo on a deserted cliff is the guarantee of having to find the solutions yourself. It’s back to basics, face-to-face with yourself: no consumerism here, what you get will come from you, and from you alone—brilliant as well as rotten methods. An adventure.

In short, we often get into rope soloing by default, we refine it for its practical side, but we stick with it out of happiness.

Pictures by Alex Needham, Kuba Klos and Denis Lejeune

olli

perso, j’ai pratiqué le solo MAA au Verdon, dans des grandes voies de 200 m, en descendant avec un stat de 200 m ou 2 stats de 100 m puis en remontant et ravalant la corde de relais en relais

la dernière que j’ai faite doit être caca boudin / durant une belle journée en octobre

des grands moments de plaisir, avec un risque zéro / que du bonheur

à ne pas faire bien sûr quand il y a du monde dans les voies …