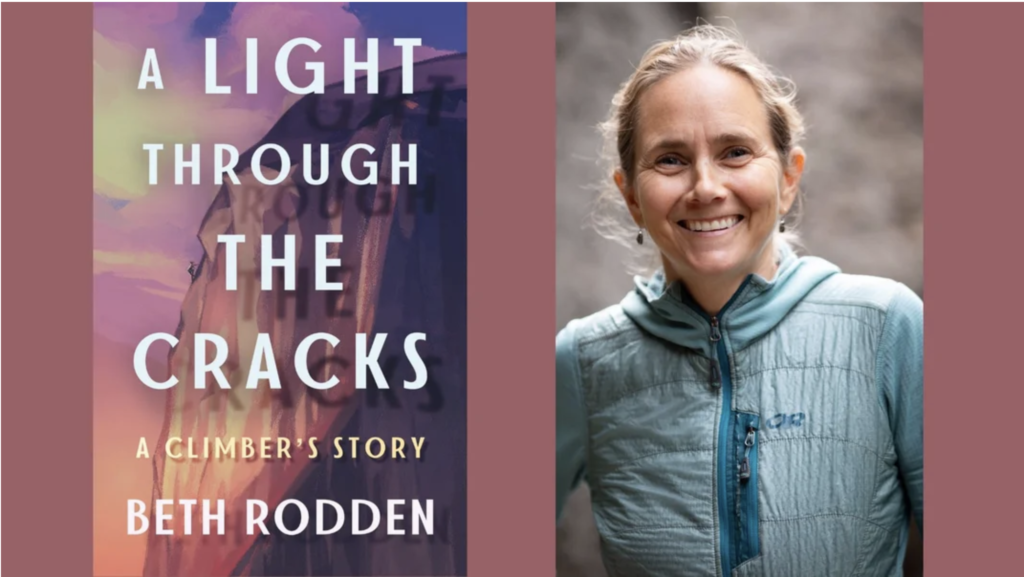

Si A Light Through the Cracks devait se résumer en un mot, le voici: insécurités. À 44 ans, la grimpeuse américaine Beth Rodden vient de publier son premier livre, une autobiographie, et le moins qu’on puisse dire est que c’est une œuvre forte.

Mon expérience à sa lecture a sans cesse été duelle: incapable de le fermer, en même temps que catastrophé par le dialogue intérieur nocif constant qui crible celle qui a ouvert, entre autres, la célèbre ligne de trad extrême “Meltdown” au Yosemite (répétée seulement 11 ans plus tard, par Carlo Traversi). Meltdown, d’ailleurs, tout un symbole sémantique pour ce livre douloureusement irrésistible: “craquage”, ou “fiasco”.

Beth Rodden a pourtant tout d’une grande. Plus jeune femme à enchainer un 8b+ avec “To Bolt or Not to Be” (en 1998, âgée de 18 ans), elle devient en 2000 la seconde femme après Lynn Hill à gravir El Cap en libre en s’offrant l’ouverture de “Lurking Fear” avec son mari de l’époque, Tommy Caldwell.

Mais oui, si beaucoup connaissent le nom de Beth, c’est encore souvent pour son association avec Caldwell, avec lequel elle a vécu une expérience on ne peut plus traumatisante au Kyrgyzstan. Lors d’une expédition, les deux grimpeurs et deux de leurs collègues furent enlevés par ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui un “groupuscule terroriste”. C’est au bout d’une semaine de fuite à travers les montagnes, de nuit et sans nourriture, que le dénouement eut lieu, lorsque Tommy poussa leur kidnappeur dans le vide.

Cet épisode occupe une place fondamentale dans la suite de l’existence de Beth Rodden. Si, au niveau du procédé narratif, j’ai personnellement trouvé les allers-retours incessants de la première partie du livre entre le kidnapping et les mois qui ont directement suivis, un peu artificiel, cette intrication montre combien l’événement a fait office de nœud gordien pour Beth. Et les pages suivantes le confirment: la grimpeuse s’est structurée en tant qu’adulte sur la base d’une peur viscérale subsumant à peu près tout.

Il est fascinant de comparer les autobiographies de l’ex-couple. Dans The Push, celle de Caldwell, l’enlèvement est traité de façon presque détachée, factuelle. Éduqué par son père à surmonter les obstacles qui se présentent à lui (“comme un vrai mec”, pourrait-on dire), Tommy fait peu cas de l’impact psychologique qu’eut son expérience kirghize. Et peut-être est-il en effet rapidement parvenu à passer outre. Mais à l’inverse, le Kyrgyzstan a littéralement structuré, ou plutôt déstructuré Beth. Il est vrai que ses insécurités remontent pour une part à l’adolescence: faire partie des meilleurs à un jeune âge, dans une industrie dont elle rappelle souvent combien elle privilégiait les hommes par rapport aux femmes (et l’apparence sexualisée chez celles-ci), pas évident à porter pour certain/es. Mais l’enlèvement les a amplifiées au centuple. À tel point qu’il m’a souvent été éprouvant, vraiment, d’être témoin de ses torrents de remise en question, d’infériorisation et autres crucifixion au regard supposé des autres. Que Beth parvienne à survivre à un tel courant de conscience relève déjà de l’exploit; alors se dire qu’elle a réussi à enchainer “Meltdown” et autres empesée, lacérée par un tel lest psychologique? Les mots me manquent…

Par rapport au Push, A Light Through the Cracks problématise la relation Caldwell-Rodden par le biais d’un long travail d’auto-réflexion et d’introspection, et parvient avec brio à mettre le doigt sur les raisons de leur rupture sans jamais peindre Tommy sous un mauvais jour (bien des années plus tard, ils sont d’ailleurs redevenus amis).

Les livres importants sont souvent cathartiques. Pour l’auteur et le lecteur. Il est évident que, par le biais de cette autobiographie, Beth Rodden poursuit sa psychanalyse et cherche ainsi à tracer noir sur blanc le chemin de sa réhabilitation. Pas professionnelle, ni réputationnelle, simplement de sa réhabilitation dans une compréhension et une acceptation de l’existence qui ne repose plus uniquement sur la phobie, la panique, la frayeur, l’impression de décevoir ou de tromper son monde. Mais A Light Through the Cracks est également cathartique pour le lecteur, en montrant combien malsaines certaines habitudes de pensée peuvent s’avérer si on leur fait trop de place.

Toujours sponsorisée à l’âge de 44 ans, Beth a réussi la gageure de passer d’athlète de très haut niveau à “metteuse en garde”, en particulier contre les dangers du REDs, dont elle a elle-même souffert et qu’elle aborde largement, en montrant en filigrane son attitude envers la nourriture tout du long.

A Light Through the Cracks prend les codes du livre de grimpeur à rebours. Alors que le genre célèbre le succès, et envisage l’échec comme simple obstacle temporaire, l’autobiographie de Beth Rodden n’évoque la réussite grimpale qu’en passant. Étonnante dynamique que celle de Beth, qui ne réussissait jamais assez pour venir à bout de son syndrome de l’imposteur ou de ses anxiétés multiples; mais qui, plus de quinze ans après le Kyrgyzstan, remariée, mère et enfin apte à verbaliser avec un psy, commence enfin à saisir qu’une vie n’est pas nécessairement un tribunal (de soi, de la performance, du regard des autres etc), mais se vit—si on lui en laisse l’occasion.

À mon avis ce livre fera date, en tout cas le devrait, et on souhaite à Beth Rodden toute l’auto-tolérance qu’elle pourra s’accorder.

(NB: le livre n’est pas encore disponible en français, mais Guérin aura sûrement son mot à dire?)

If A Light Through the Cracks could be summed up in one word, it would be: insecurities. At 44, American climber Beth Rodden has just published her first book, an autobiography, and it is a powerful one, to say the least.

My experience of reading it has always been twofold: unable to close it, while at the same time feeling devastated by the constant noxious inner dialogue that riddles the climber who opened, among others, the famous ‘Meltdown’ extreme trad line in the Yosemite (repeated only 11 years later, by Carlo Traversi). ‘Meltdown’, incidentally, proving to be a rather apt semantic symbol for this painfully compelling book.

Beth Rodden had all the makings of a great climber. The youngest woman to climb an 8b+ with ‘To Bolt or Not to Be’ (in 1998, aged 18), in 2000 she became the second woman after Lynn Hill to free-climb El Cap, by grabbing the first ascent of ‘Lurking Fear’ with her then husband, Tommy Caldwell.

But yes, if many people know Beth’s name, it is still often for her association with Caldwell, with whom she shared a traumatic experience in Kyrgyzstan. During an expedition, the two climbers and two of their colleagues were kidnapped by what is now known as a ‘terrorist group’. It was after a week’s flight through the mountains, at night and without food, that the denouement came, when Tommy pushed their kidnapper into the abyss.

This episode plays a fundamental role in the rest of Beth Rodden’s life. While I personally found the incessant back-and-forth between the kidnapping and the months that immediately followed in the first part of the book a little artificial in terms of narrative process, this intertwining at least shows the extent to which the event acted as a Gordian knot for Beth. And the following pages confirm it: the climber has structured herself as an adult on the basis of a visceral fear that subsumes just about everything.

It is fascinating to compare the respective autobiographies of the ex-couple. In Caldwell’s The Push, the kidnapping is treated in an almost detached, factual way. Educated by his father to overcome the obstacles he faced (‘like a real man’, one might have said), Tommy pays little attention to the psychological impact of his Kyrgyz experience. And perhaps he did quickly get over it. On the other hand, Kyrgyzstan literally structured, or rather destructured Beth. It’s true that some of her insecurities date back to her adolescence: being one of the best at a young age, in an industry that she often reminds us favoured men over women (and the sexualised appearance of women), is not an easy thing to bear for some. But the kidnapping amplified them a hundredfold. To such an extent that it was often really hard for me to witness her torrents of doubting, low self-esteem and other crucifixions in the eyes of others. That Beth managed to survive such a stream of consciousness is already no mean feat, but to think that she managed to string together ‘Meltdown’ and the rest while burdened by such psychological ballast? Words fail me…

Compared to Push, A Light Through the Cracks problematises the Caldwell-Rodden relationship through a long process of self-reflection and introspection, and brilliantly manages to pinpoint the reasons for their break-up without ever painting Tommy in a bad light (many years later, they are friends again).

Important books are often cathartic. For the author and the reader. It’s clear that, through this autobiography, Beth Rodden is continuing her psychoanalysis and seeking to lay out in black and white the path to her rehabilitation. Not professional, not reputational, simply her rehabilitation into an understanding and acceptance of existence that is no longer based solely on phobia, panic, fear, the impression of disappointing or deceiving the world. But A Light Through the Cracks is also cathartic for the reader, showing just how unhealthy certain habits of thought can turn out to be if given too much space.

Still sponsored at the age of 44, Beth has succeeded in the challenge of going from very high-level athlete to ‘cautionary speaker’, in particular about the dangers of REDs, from which she herself has suffered and which she discusses extensively, showing her problematic attitude towards food throughout.

A Light Through the Cracks takes the codes of the climbing book in reverse. While the genre celebrates success and sees failure as a temporary obstacle, Beth Rodden’s autobiography only mentions climbing success in passing. This is a surprising dynamic for Beth, who was never successful enough to overcome her impostor syndrome or her multiple anxieties; but who, more than fifteen years after Kyrgyzstan, remarried, a mother and finally able to talk to a psychologist, is finally beginning to understand that life is not necessarily a trial (of oneself, of performance, of the gaze of others and so on), but can be lived peacefully-if given the opportunity.

In my opinion, this is a landmark book, or at least it should be, and we wish Beth Rodden all the self-tolerance she can muster.

Philippe

Dommage que l’auteur de cette intéressante critique soit inconnu… Pourquoi ne pas signer le texte?